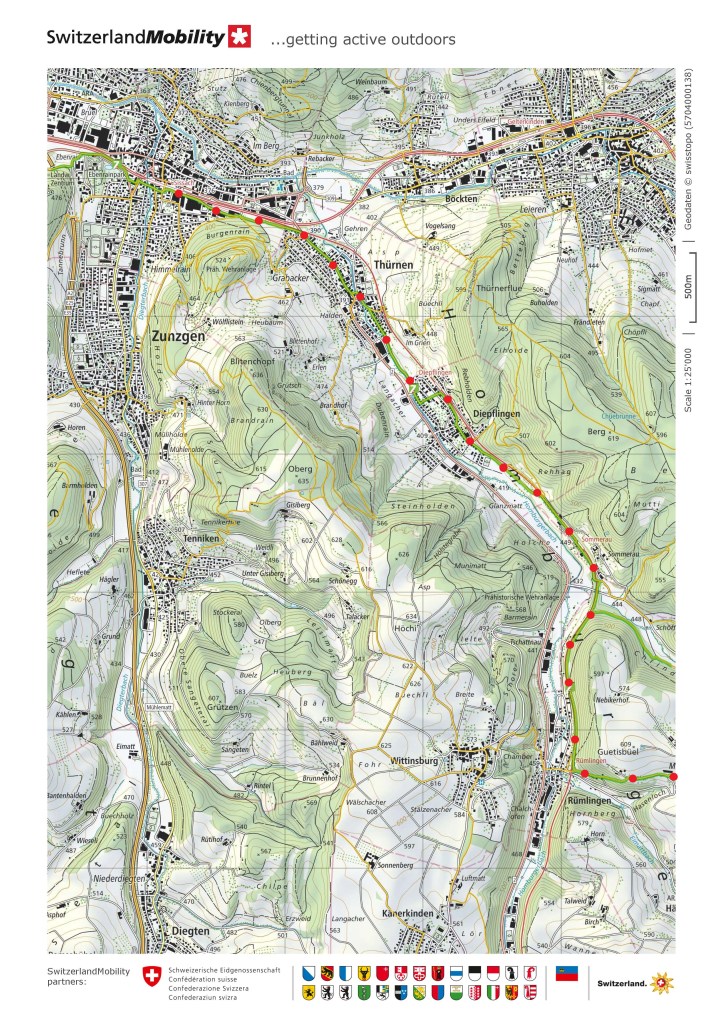

This next stage of the Via Gottardo would take me across the mountains to Olten. The railway has two routes for getting from Sissach to Olten. There is the main line, and then there is a smaller single track route that goes up the valley of the Homburgertal. That second rail route would be a feature of my walk to Olten.

But first, I had to get out of Sissach. I followed the route from the station, passing the sheds where the Swiss Federal Railway houses some vintage carriages and locomotives. And then the route went over a small hill to reach Thürnen. To call Thürnen a village would be to afford it a compliment. It is really too small for that. Mostly, it is streets of modern suburban housing, with just the nucleus of a village at its core.

I went quickly through Thürnen, my route staying close to the Homburgerbach stream. There are just a few fields that separate Thürnen from the next village on the route: Diepflingen. Diepflingen is even smaller than its neighbour, but it does merit a station on the railway line, which Thürnen does not. Unlike Thürnen it seems to have no centre to the village, being almost entirely composed of modern housing areas. And so I kept on going. Outside Diepflingen, the track ascends slightly, and so I came to the railway.

This railway line was actually the original of the two lines that currently join Sissach and Olten. Right up until the beginning of the nineteenth century, there was not even a proper road going over the Hauenstein pass to link Basel to Olten. The road was built first, and then in the 1850s came the railway. It was not until 1916 that what is now the main line was opened, and in the interim, the Läufelfingen route was the only rail link from Basel to Olten. The current main line is sometimes referred to as the base tunnel route, and had significant advantages over the Läufelfingen route, as the latter has to climb over 150m on the way. As a result, the Läufelfingen line has been downgraded over the years. There was a proposal to close the line a few years ago, but under Switzerland’s system of direct democracy, a referendum in 2017 forced the Swiss Federal Railways to keep the line open until 2021. After that, the future is uncertain.

But none of that was going through my mind as I followed the path alongside the railway to come to Sommerau station.

For many years, Sommerau and Läufelfingen were the only permanent stations in this valley. It is somewhat incongruous, as Sommerau itself is not even a village. It is best described as a farming settlement. Other villages on the line did not get stations until well into the twentieth century. That is why Sommerau station, despite being almost in the middle of nowhere, has a permanent brick built station building. The nearby goods shed is of wooden construction and looks like it was abandoned sometime about 1950. Today, the station building is actually home to a medical massage business. The ticket office and waiting rooms have long since ceased to function.

From Sommerau, I continued alongside the railway line. My route followed a track, with the railway just below to my right. And following the railway meant no steep gradients, which made for a good walking pace. That tack brought me to Rümlingen.

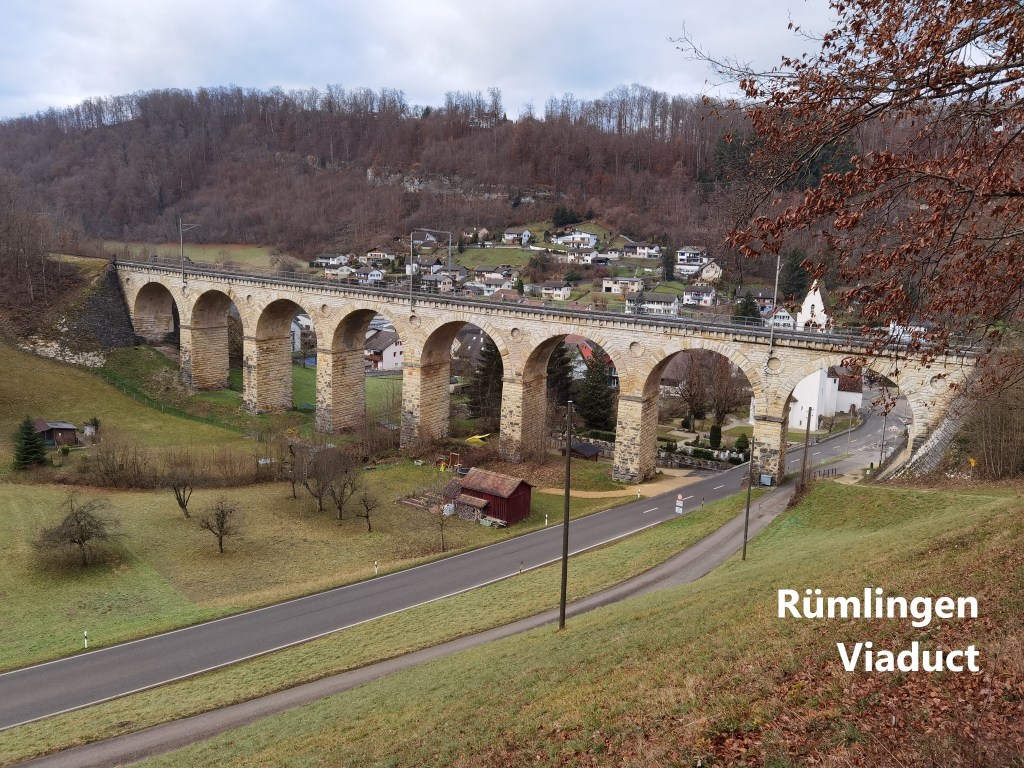

Following the trail, I turned left at Rümlingen, going uphill a little, but stopping just short of the woods to get the best view of the Rümlingen viaduct. This feat of engineering was built between 1856 and 1858. It was unusual at the time to build viaducts of stone. Iron construction was cheaper, but stone lasts longer. The engineer leading the construction of the line, Karl von Etzel, is reported to have taken inspiration from similar viaducts in Austria. It is 128m long and 25m above the valley floor. Whereas the iron viaducts have almost all been replaced with stone in the twentieth century, the Rümlingen viaduct remains. It is the oldest viaduct in Switzerland still in its original state. With a history like that, I just had to check the train timetable, and I was delighted to find that if I waited just four minutes, I would see a train go across.

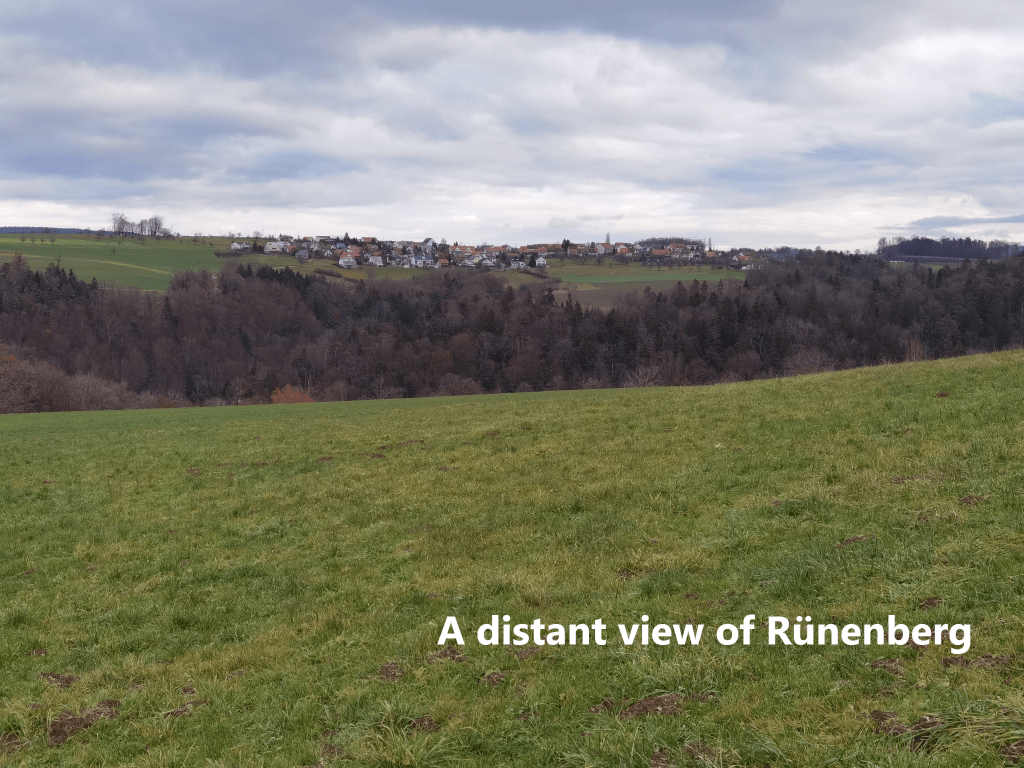

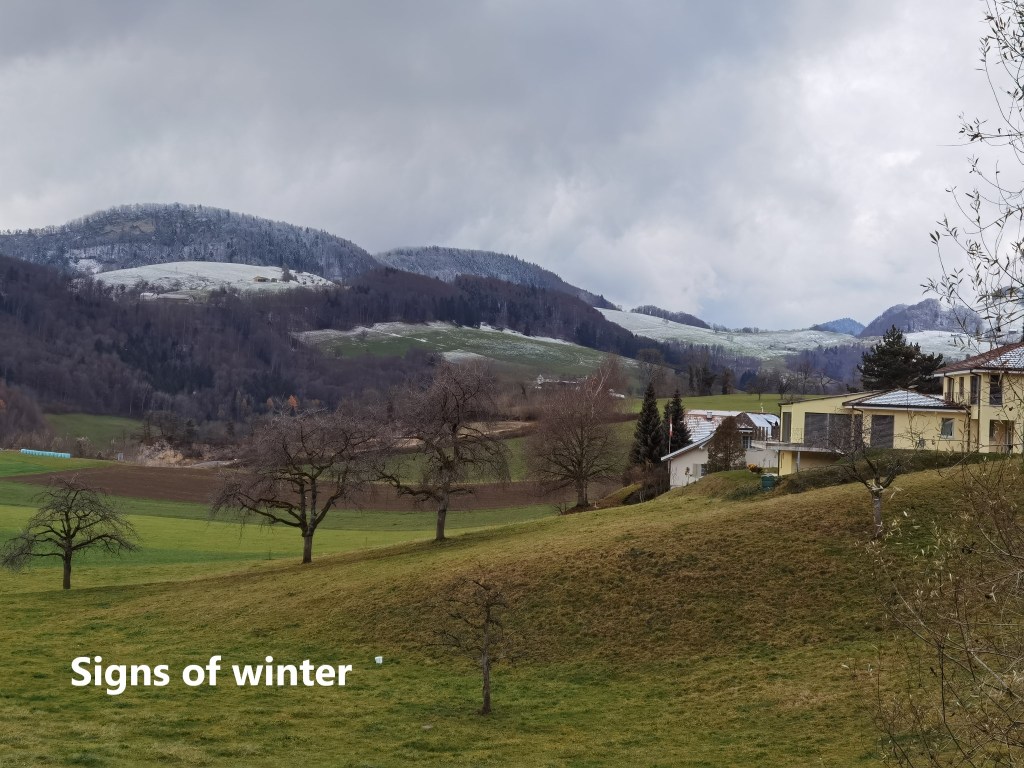

I left Rümlingen, going up into the hills to the east. Soon I was walking through upland farm country. Across the fields, I could see the village of Rünenberg. Here and there, isolated trees have adopted their winter skeletal form. In some of the distant higher spots, I could see a light frosting of snow. It is indeed winter now.

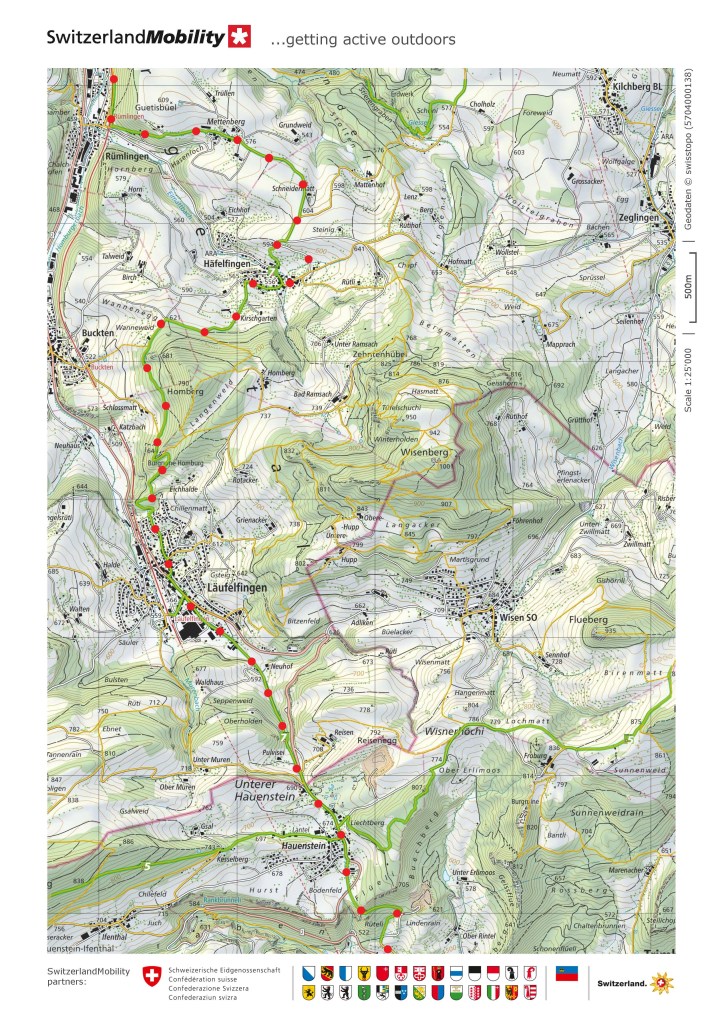

I went on, and came to Häfelfingen, a small mountain village. It is a pretty little place, though it seemed to be asleep as I passed through, with a lone cyclist the only person that I passed.

I went on through the village, and the higher ground beyond. It was easy going, through fields at first, and then along the edge of the woods. As I turned to go south again, the village of Buckten came into view. Then there were the Rütiflue cliffs, before I came to the castle at Homburg.

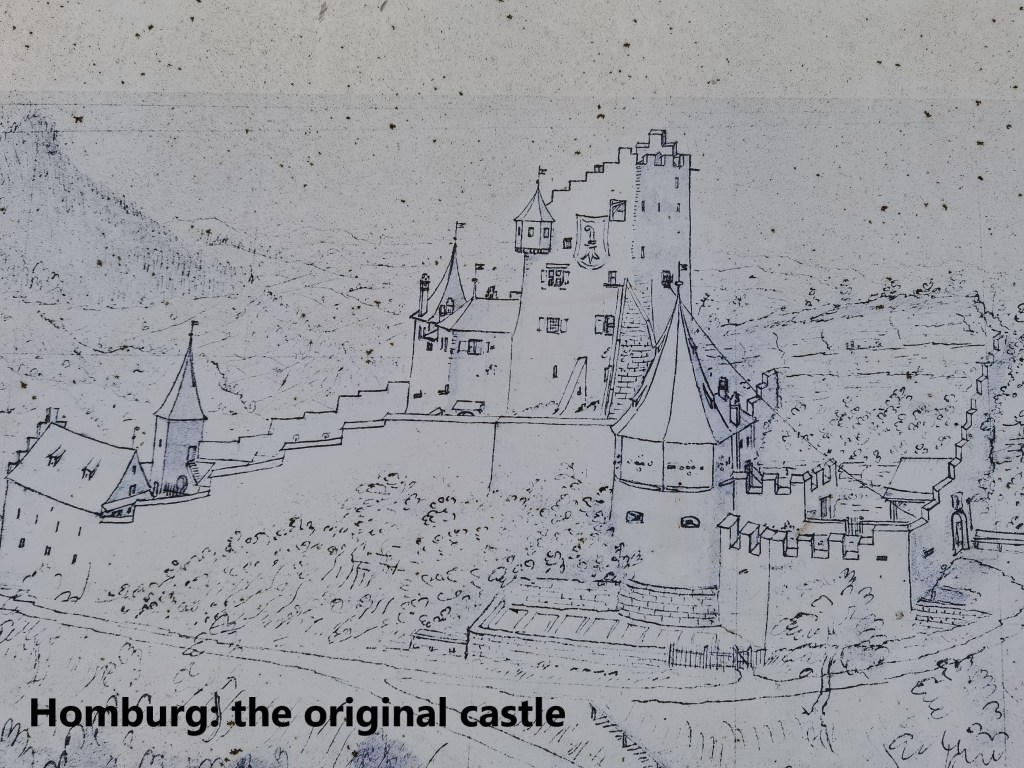

The castle at Homburg was built by Count Herman von Froburg in 1240. He named it Neu-Homburg in honour of his wife who was heir to an estate called Homburg in the Fricktal area. Over time, the prefix was dropped, and the name Homburg remains, giving that name also to the stream that runs through the valley, the Homburgerbach, and indeed the valley itself, the Homburgertal. The von Froburgs were not rich enough to maintain the castle, and in 1300 they needed money. The castle was sold to the Bishop of Basel along with the surrounding villages and estates. A hundred years later, the bishop sold it on to the City of Basel. The city installed a bailiff to oversee the castle and its estates, and so things remained for almost 400 years. But in the 1790s, after the French Revolution, there was a lot of agrarian unrest in Basel canton. Things came to a head in January 1798. With the threats of attacks on the castle, the bailiff took what he could of value, and fled. The peasantry attacked and ransacked the abandoned castle before setting it on fire. After the fire, the ruin passed into private ownership, and it was actually used as a source of stone for other building work. The ruin became heavily overgrown and remained in disarray until the Basel Landschaft authorities organised some restoration and conservation in 1937. There was further work done by Basel Landschaft in the years 2008 to 2010 to preserve the site and make it the imposing ruin that it is today.

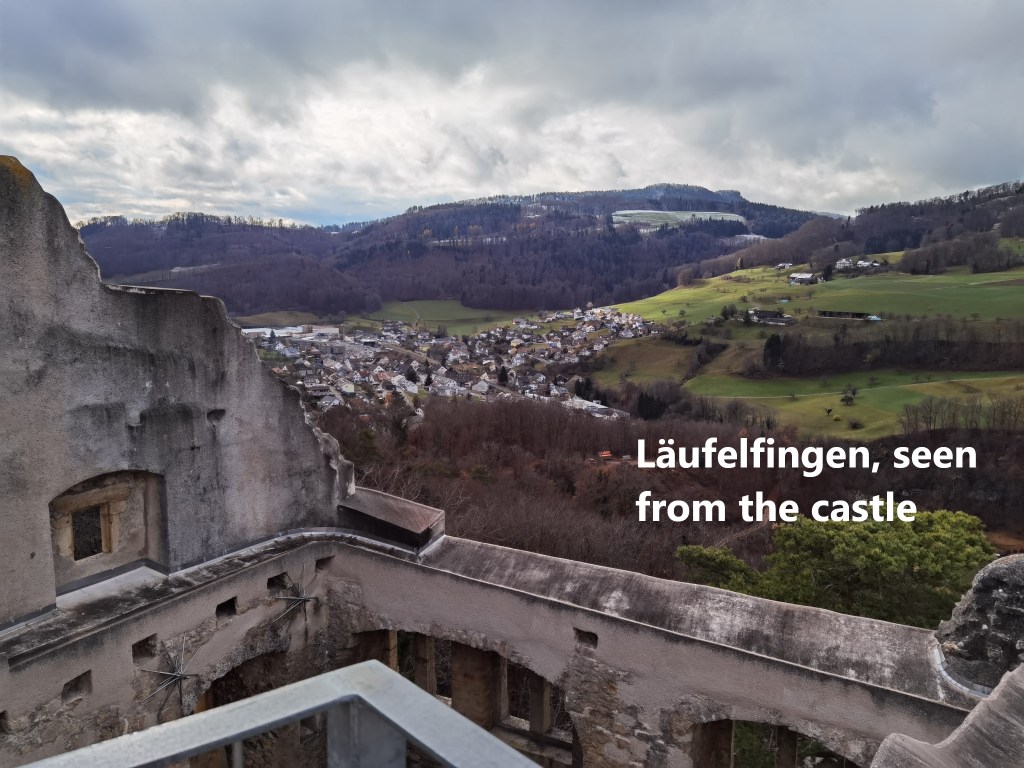

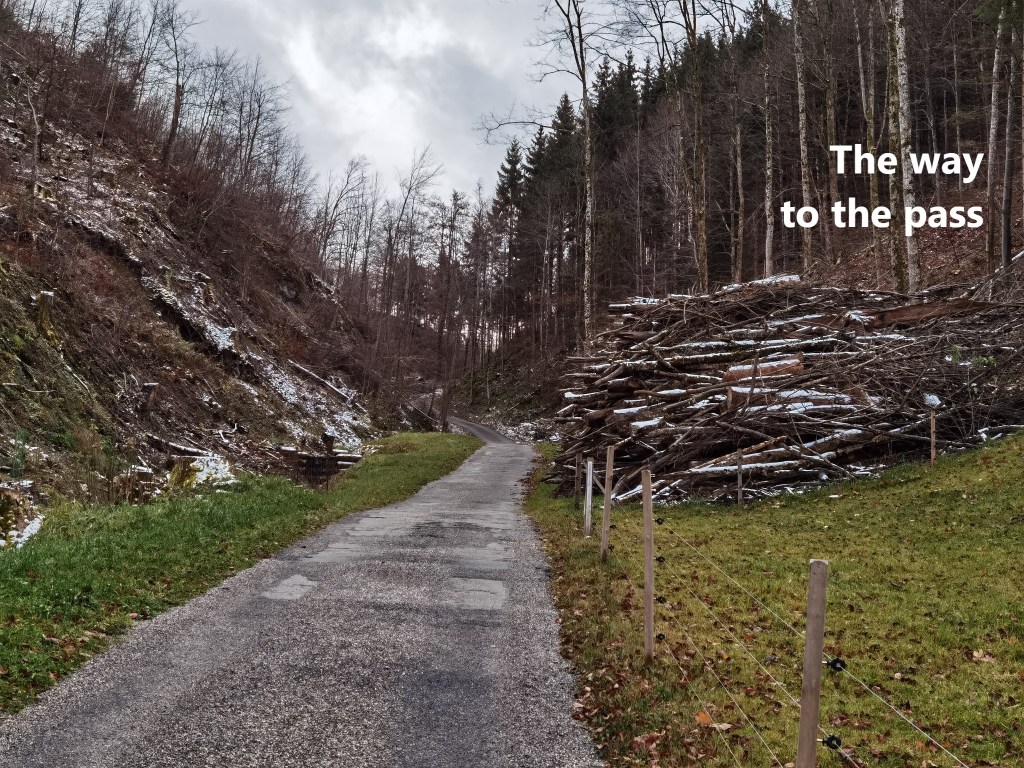

From Homburg, my route took me downhill to the village of Läufelfingen. I was back close to the railway again, but whereas it goes into a tunnel to get through the mountains towards Olten, I had to take the old route to the pass. This was the highest point on my route, and there were just the faintest traces of snow on the way.

The pass is also the point where I left Basel Landschaft canton behind and moved into Solothurn. Once over the pass, it was downhill again to the village of Hauenstein. I went through Hauenstein before when I was walking the Jura Höhenweg. There is a restaurant in the village, the Ate Schmitte, but it seems that every time that I come to Hauenstein it is closed. Last time, I was too early for its opening season, and this time too late. A sign said that it would be closed for winter from 1st November. But even when closed, the Alti Schmitte has an interesting array of classic cars outside in various stages of disrepair.

From Hauenstein, I went on downhill. Away to the west, I could again see a light frosting of snow on the hills. And then I came to the Felsdurchbruch. At first, this looks like a natural cleft in the rock, but it is not. People having been using the Hauenstein Pass as a route through the Jura Mountains for centuries. At that time, it must have been no more than a mule track. In the 1560s, as part of improvements to the track, the Felsdurchbruch was made. It has been there for over 450 years now, so it has become natural in appearance.

As I went on, there was an occasional snowflake falling. It was not enough to say that it was snowing, more a portent of something to come. I kept going, with the trail continuing to follow that centuries old track.

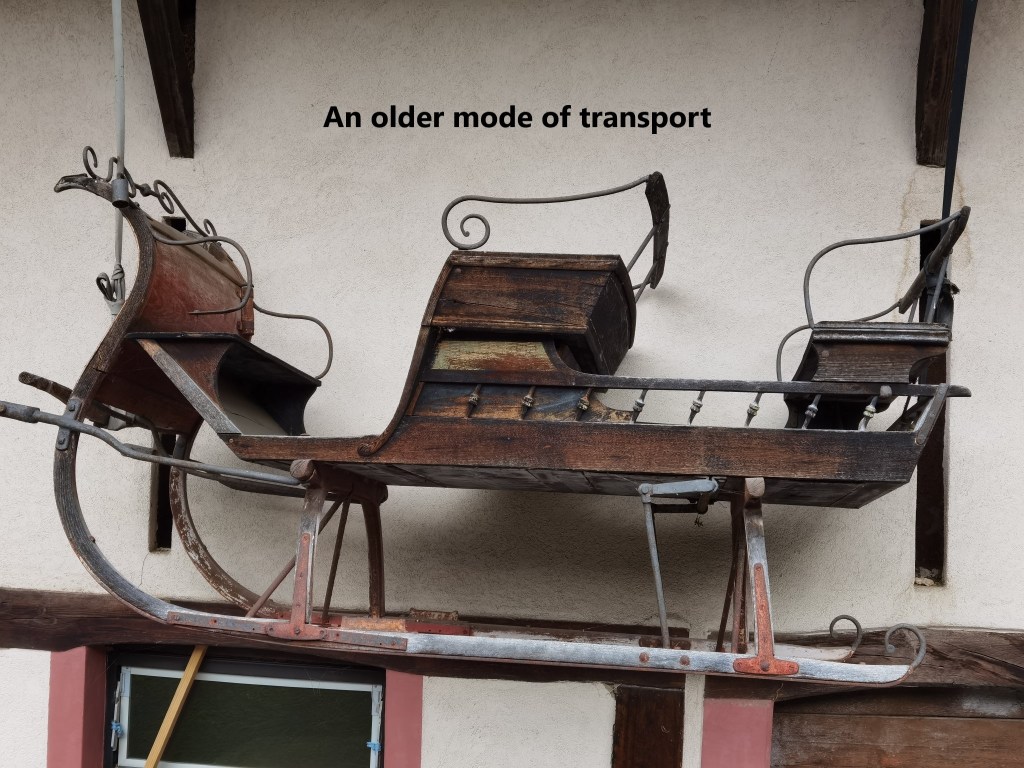

It wasn’t long, though, before I came to a real road, where a monument commemorates the first true road construction through the pass. It was built as a joint effort by the cantons of Basel Landschaft and Solothurn, and was opened in January 1830. Where the old medieval track had gradients of up to 24%, the steepest gradient on the new road was 5%, making it much easier for wheeled vehicles to go through the pass. The road was more than nine kilometres long, and took two years to build, costing 330,829 Francs.

I followed the road, rejoining the railway line for a short time, and then coming into the city of Olten. There has been a settlement here since Roman times. Even then, it was the junction of routes going north to south and east to west. The settlement waxed and waned over the centuries, including disastrous fires in 1411 and 1422. At the time of the 1422 fire, the town was owned by Basel, but Basel was not interested in rebuilding, and so sold the town to Solothurn in 1426. The town sided with the peasants in the wars against authority in the seventeenth century. It again supported an uprising in 1814, this time against the Swiss Restoration after the defeat of Napoleon. It seems that Olten has a history of supporting anti-authoritarian movements.

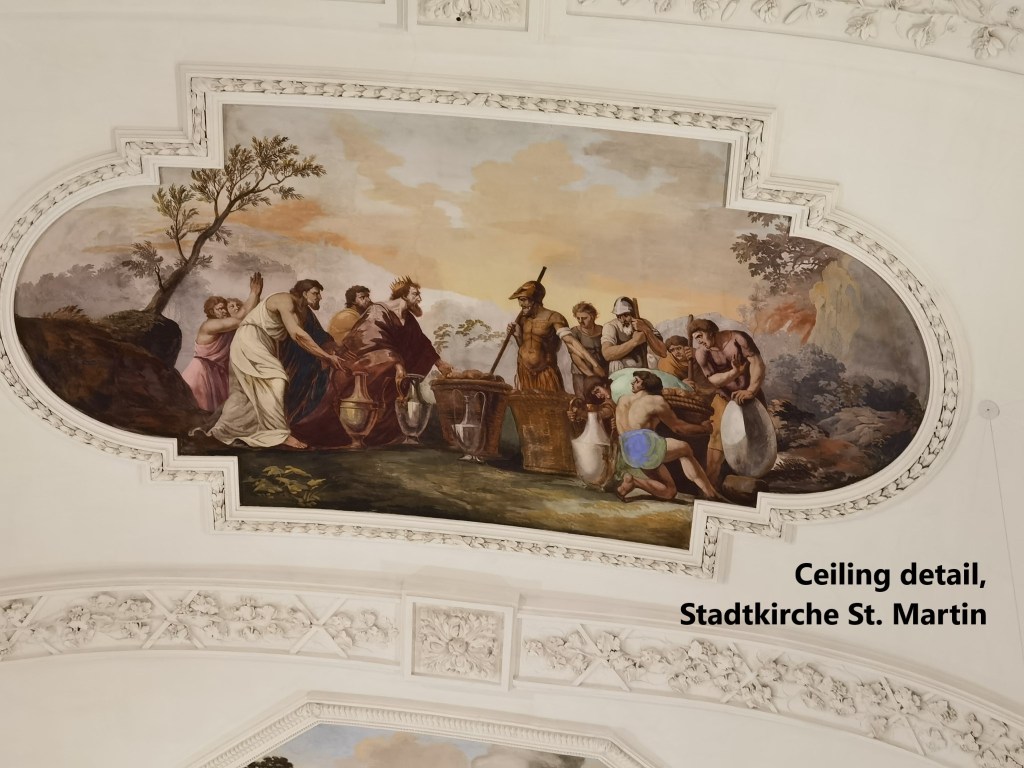

Entering the city, I came to the Aare. I last saw this river in my wanderings through Bern canton on the Trans Swiss Trail. But in Olten, it is much bigger. I had a little bit of time to spare, so I went into the older part of the city. My first call was at the Stadtkirche, dedicated to St. Martin. The building dates back to the middle of the nineteenth century.

After that, I took a walk through that part of the town to the wooden covered bridge on the Aare. I passed the Stadtturm, which is all that remains of an older church. That older church was built in 1521, but over the years deteriorated to the point that it had to be demolished in 1844, leaving only the tower.

After crossing over the covered bridge, it was only a short walk to the train station. I could have got a train on the main line to Basel almost immediately, but I decided to wait for one that would take me back through the Homburgertal. After going through the tunnel under the Hauenstein Pass, it was snowing when I reached Läufelfingen station. It was still snowing as I went over the Rümlingen viaduct, all very different from when I stopped there earlier in the day. I had been lucky with the weather on my journey. I had to change trains in Sissach, which makes this line less convenient than the main Olten-Basel line. But this is a line with an uncertain future, so it needs all the travellers it can get to justify its continued use.

Finally, my total step count for the day was 38,441.